GDPR Article 30 Record Keeping: What’s The Point of Keeping Records on Your Data Processes If You Don’t Know Where Your Data Records Are?

GDPR introduces a number of challenging obligations for enterprises, ranging from data subject rights to consent management. One of the more labor-intensive obligations is the Article 30 requirement for processors and controllers of personal data to keep records of processing activity. Usually referenced as the “Article 30 Record Keeping requirement”, this obligation places a responsibility on companies to accurately account for identity data they process. While one purpose of the record keeping requirement is to provide DPA regulators necessary proof of compliance, the broader goal is to help companies become better stewards of customer and employee data.

As a record keeping requirement of data processing, Article 30 is often associated with “data flow maps” which document and diagram processing of personal data from collection through disposal. When done correctly, they provide regulators and GDPR subject companies a way to codify processing activities and ensure that necessary artifacts like purpose-of-use and category-of-data are properly captured. Further, the regulation encourages organizations to leverage record keeping in order to capture additional information necessary to protect EU residents and citizens. Article 30’s purpose is to create an unambiguous record of how personal data is processed by an organization. However, there remains a significant ambiguity at its heart: where does knowledge of data being processed actually originate?

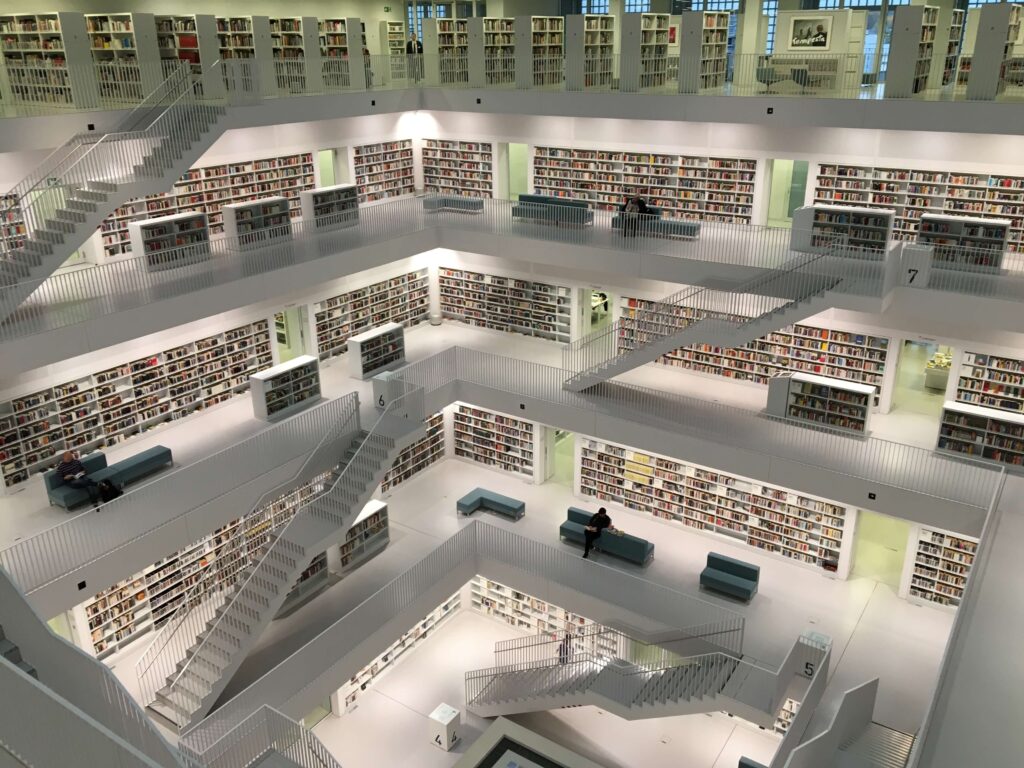

Digital Dreams And Analogue Compromises

The most trivial way in which an organization can discover detail on their data processing activities is to ask the stakeholders responsible for said processing. After all, they should be able to provide attestation as to what data they collect, purpose of collection and use, retention, etc. And if humans had infallible recollections and perfect knowledge, this method of information gathering and record keeping would represent an accurate accounting of actual data processing. Unfortunately, people are not perfect in their recollection of where they put their car keys, let alone where they put their data.

People forget. People change jobs. People misinterpret. People who own applications which process data rely on other people to build those applications. “People Are People” as Depeche Mode accurately observed. They are not computers.

Relying on interviews and surveys to discover what personal data an organization collects and processes may be better than nothing, but better than nothing is not the intended aim of GDPR’s Article 30. In the Information Age, an accurate method of determining where digital information is actually collected and processed is a must have. Figuring out what data is stored and processed on a computer should be determined by an actual computer. And, as Depeche Mode might say: “People Are Not Computers”.

Don’t Trust, Verify

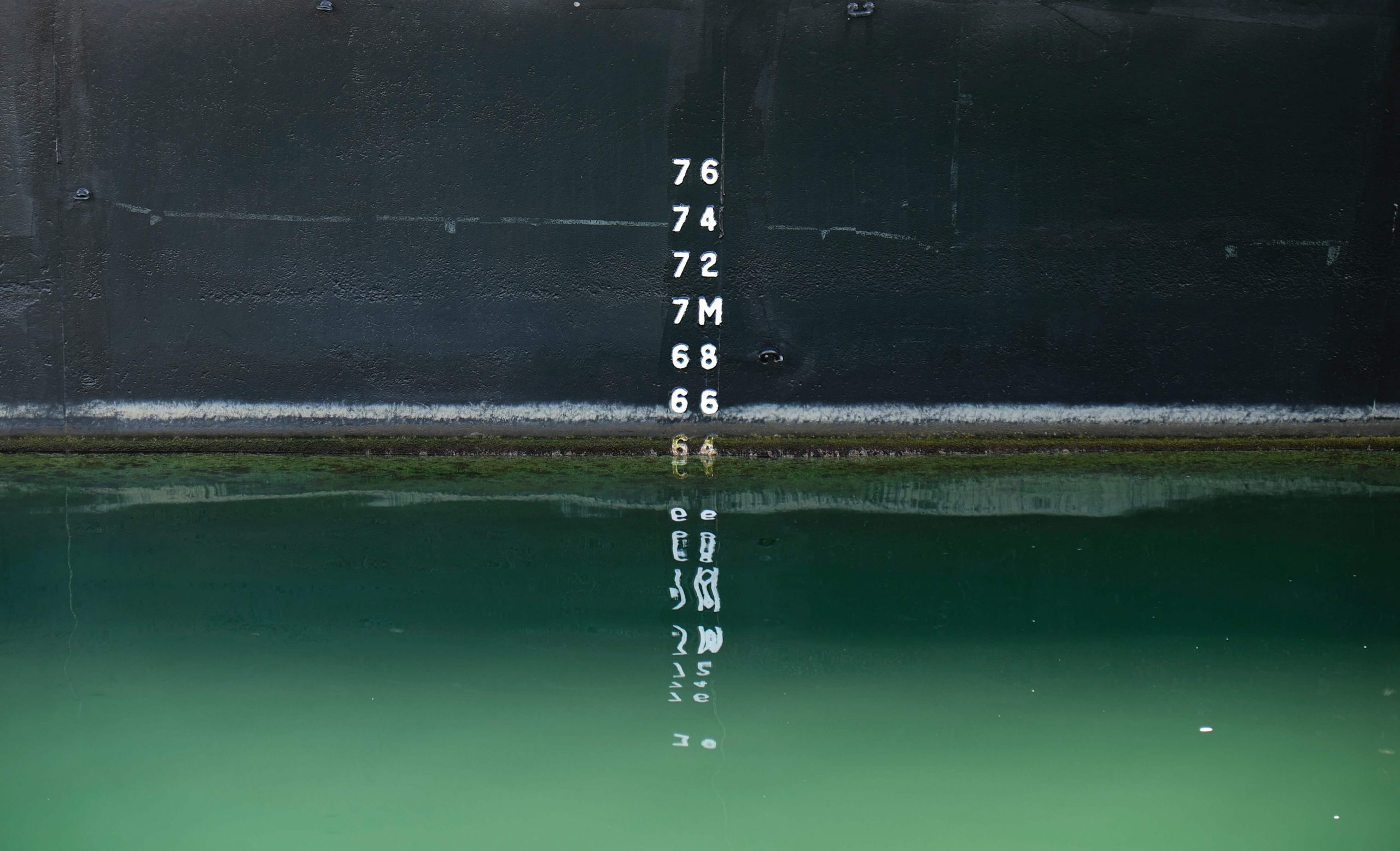

To a degree, GDPR is analogous to financial regulations. However, instead of focusing on integrity of financial transactions and affected institutions, the focus is on integrity of data processing and affected data subjects (people). Data is to GDPR what financial transactions are to Basel III. This is only fitting in the Information Age, where data is the currency of commerce and communication. And, like any financial regulation whose measurement of compliance depends on accurate accounting of the substance which underpins it, GDPR requires accurate accounting of data in order to be both effective and measurable.

Recollections are not records. Without accurate data accounting there is no audibility, and without audibility how can one verify compliance? For a data protection regulation like GDPR to be useful, verification needs to be data-driven. After all, you can’t protect what you can’t find. BigID is the first product on the market to give organizations an ability to not just find all personal data belonging to an individual, but to also use that data mapping in order to record data flows based on actual data processing. Using BigID, organizations can build and maintain data processing records which reflect real data records using the latest in machine learning, and not just paper questionnaires.

GDPR asks companies to safeguard information of their data subjects. Article 30 asks organizations to provide evidentiary proof that every digital process requiring collection and processing of personal data is properly accounted for. But to make it truly accountable to individuals ie data subjects, record keeping of data processing needs to be based on actual data. BigID, for the first time, gives companies a way to meet this obligation based on real, and not just recalled, data records.